【宏觀視野】Proposal for an East Asian Research Institute

Alan T. Wood

Professor of History,

University of Washington Bothell.

Introduction

The last article I wrote for the Institute for Advanced Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences discussed the decline of the humanities in contemporary schools and universities all over the world. I concluded by suggesting that although universities are excellent tools for analysis, they are not excellent tools for synthesis. To be sure, analysis is essential for understanding problems by breaking them down into bite-size chunks. To solve those problems, however, we need a process of synthesis that connects those chunks together into fundamentally new wholes. Now, the need for synthesis is greater than ever. Because the challenges facing the world today are global and interconnected, they require synthesis on a scale never before faced by human civilization. Among them are climate change, environmental degradation, loss of biodiversity, nuclear proliferation, crime, and disease—all of which transcend national boundaries and academic disciplines. To fashion solutions to these global challenges will require the best minds in the world working together in institutions that foster creative breakthrough thinking of the highest order.

In this essay I therefore propose a new kind of research institute in East Asia whose purpose would be to bring together the most visionary intellectual, political, social, and economic leaders in Asia to address the fundamental issues facing the modern world. The research institution I have in mind would be a catalyst for a new level of synthesis in East Asia that would combine the wisdom of the past with the knowledge of the present. It would contribute to East Asia assuming a role of global intellectual leadership commensurate with its growing economic and political power. The world desperately needs the holistic, organic, long-term, and sustainable-systems worldview of traditional Asian culture to balance the atomistic, mechanistic, short-term, and reductionist worldview of the West. It is not that the Western worldview is wrong, but that it is only partially right. Its great achievement was to foster the scientific and industrial revolutions, which have vastly increased the scale of opportunity for human civilization. But it has also produced consequences that now imperil the well-being of the planet. What we need now is a new synthesis, a re-birth, a renaissance of the classical Asian worldview that can lay the foundation for a sustainable system of global governance.

What kind of institution could provide the incubator for such an effort of conceptual and synthesizing creativity? As I mentioned above, it is difficult for existing university structures in general to play this role. Their primary purpose is to preserve and transmit human knowledge, and their intellectual assumptions are inherited from the past. They are also, by necessity, complex bureaucracies that are intolerant of risk and failure. Responding very slowly to changes in the world around them, they operate within the boundaries of the specialized academic disciplines into which they have artificially divided human knowledge.

If not a university, then, what other kind of institutional structure could provide the conditions for such a renaissance? To answer that question, I look at some specific examples and common characteristics of extraordinarily creative periods in world history—moments that deserve to be called a renaissance. I then consider some other examples and common characteristics of modern research institutions that have successfully fostered breakthrough innovations. I conclude by making some suggestions for how we might try to organize such a research institute in the future.

Examples and common characteristics from earlier history

I. Examples

Classical Athens gave birth to the main categories of thinking and some of the greatest works of art in Western civilization, and yet it embodied a number of paradoxes. The most astonishing was its relatively small size and modest geographic scope, far out of proportion to its historic impact. Its relatively small size, however, may have crucial to its ultimate success. It was small enough to preserve individual autonomy, promote useful conversation, stimulate new thinking, and above all, explore ideas freely without the constraints that come from a centralized state and a big administrative bureaucracy. The Roman Empire lasted much longer and had a vastly greater population and resources. Yet it produced only a tiny fraction of the intellectual and artistic work of ancient Athens.

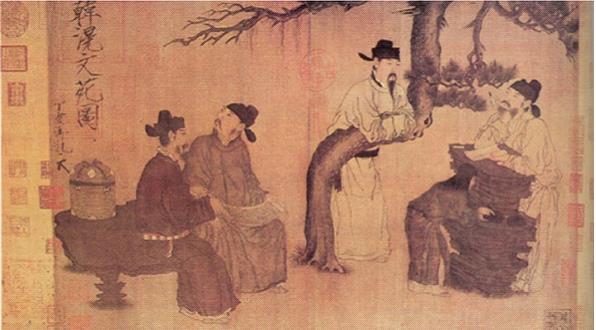

Song China witnessed one of the most creative moments in Chinese intellectual and artistic history. It was a remarkable period of freedom, fostering a virtual renaissance of thinking that was paradoxically rooted in a revival of the Confucian heritage. The Song also gave rise to the institutional revival of the academy, shuyuan 書院, and the charitable estate, yitian 義田, both of which represented a remarkable resurgence of civil society in the Song that balanced considerable autonomy with integration into a larger system of shared values. The most significant of the academies, for our purpose, was the White Deer Grotto (白鹿洞) of the philosopher Zhu Xi 朱熹. There he developed his majestic synthesis of the Buddhist, Daoist, and Confucian worldviews that dominated Chinese thinking for the next thousand years. And there also was recorded his famous series of conversations with the philosopher Lu Xiangshan 陸象山. The Song also benefited enormously from a paradoxical balance of diversity and unity—openness to a whole range of diverse ideas that had poured into China via the Silk Road during the previous thousand years, while simultaneously sharing a profound sense of cultural unity that pervaded all aspects of Chinese life. Then, as well, there existed in the Song a deep confidence in the power of the moral official to govern and even to transform the entire society.

Renaissance Florence, also small, was the center of a large network of prosperous city-states that transformed European culture by drawing deeply—and paradoxically—from the well of knowledge inherited from the past. As the focal point of the European Renaissance, it sparked the rise of classical humanism and (once again) rested on a profound sense of confidence in the power of the human mind to change the world. Here as well, trade became the agency of introducing a whole host of diverse stimulants into Italian life, as well as vast wealth. The Medici family became great patrons of the arts in Florence, as did other families in other autonomous city-states. It was a fascinating convergence of capital and creativity. At their height, these city-states were self-governing republics. Freedom provided the incentive and the opportunity to experiment, as well as a willingness to fail in pursuit of something hitherto unachieved or imagined.

The Royal Society in England, my last example from the more distant past, was formed in 1660. It was a key factor in promoting the Scientific Revolution. It filled a void in interdisciplinary communication among early scientists that universities, with their bureaucratic structure and intellectual conservatism, were unable to provide. It was relatively small, but at the same time it was integrated into a much larger conversation that included continental Europe as well. It looked backward and forward simultaneously. It benefited from complete freedom to think and explore ideas without regard to any bureaucratic imperatives. It was diverse in many ways, bringing together people with remarkably different kinds of expertise into the same conversation. It wasn't put off by failure, and it was deeply confident in the power of human reason to prevail over all obstacles. In France during the Enlightenment, a similar void was filled by the informal salons of Paris that brought the great minds of the day together in conversation.

II. Common characteristics. What lessons can we draw from the above examples? In the deep past, successful moments of extraordinary intellectual and artistic creativity appear to share a complementary and paradoxical balance of opposites.

Big and small. They were all integrated into a large network of interconnected cities and states capable of providing resources, continuity, and protection. All benefited from commercial prosperity that provided time and energy for intellectual pursuits. At the same time, they were also small and non-bureaucratic. It is not that the qualities of bureaucracy are all negative, but that the attributes of specialization, efficiency, control, fairness, process, stability, and loyalty that bureaucracies must have in order to succeed also discourage innovation and creativity. Creative institutions transcend specialization, tolerate inefficiency (because creativity requires a high tolerance for risk and failure), accept a degree of uncontrollability (because creativity requires freedom), permit a degree of unfairness (because creativity doesn't follow the rules—it invents new rules), avoid process (because ideas come from nowhere), tolerate instability (because creativity is inherently out of the ordinary), and allow for some degree of disloyalty (because creativity does not always obey hierarchy).

Old and new. The creative process is a mystery. Nowhere is that more apparent than in the above examples, which almost always combined a revival of classical ideas with wholly new ways of thinking. Perhaps that paradox is captured best in the two English words “invention” and “inventory,” which share the same root but convey a contrary image of looking both forward and backward simultaneously.

Freedom and authority. One of the central paradoxes of life itself is the complementary relationship between the contrary concepts of freedom and authority. Rules and laws—the manifestations of authority—provide the context within which freedom can exist and thrive. Too much authority, however, produces tyranny, just as too much freedom produces anarchy. The challenge for every organization is how to find the appropriate balance, given the constant pressures to favor one over the other.

Diversity and unity. Absolutely essential to any moment of creative expression is openness to a diverse array of ideas and ways of thinking. In the historical examples above, that diversity was provided in large part by exposure to broad networks of trade and communication which provided intense stimulation and incentives to explore novel possibilities. At the same time, there also has to exist a unified core of language and outlook and focus that permits effective communication and collaboration. Unity and diversity are part of a complementary whole.

Success and failure. As a historian, I am repeatedly struck by the tendency of successful organizations—whether they are dynasties, countries, or companies—to be undermined by the very qualities that made them successful. Not only does success lead to complacency, but it also inhibits management from seeing new challenges, especially those that might disrupt existing practices. A corporate culture that discourages risk and failure usually appears very early on in successful organizations as they build complex bureaucracies. When that happens, when people start to avoid risk and the possibility of failure, creativity suffers. The great challenge is therefore to encourage failure in the midst of success while simultaneously forging success out of the crucible of failure.

Confidence and humility. Here again, the relationship is a mystery. In all the periods mentioned above, there was a supreme confidence in the power of the human mind to improve the world. Without that confidence, people would not take risks. In the end, however, this confidence must also come with a deep and profound sense of humility that allows us to appreciate a larger universe full of wonders that transcend our poor ability to reason and understand. Without humility, curiosity would shrivel up, and pride and complacency would set in very early to blind us to what is happening around us. The great challenge is to be both confident and humble.

Examples and common characteristics from modern times

In addition to manifesting many of the paradoxical characteristics mentioned above, successful organizations in modern times have demonstrated an unusual quality of intellectual leadership. One of the best examples is Cai Yuanpei 蔡元培, President of Beijing University between 1917-1922. At that time, the university was new, and it was small. Cai brought to the campus an exceptionally diverse array of the best minds in China, regardless of political orientation, discipline, or formal degree, in order to stimulate conversation and debate on the future of China. That brief moment of creativity and innovation, which came to be called the May Fourth renaissance, lasted for only a few years, but it became the catalyst for the main intellectual trends of the twentieth century in China. It has never been equaled since. Cai Yuanpei also went on to found two other institutions that became major intellectual and cultural centers: what is now the Academia Sinica in Taiwan and the Shanghai Arts Conservatory in China.

If Cai Yuanpei is an example of visionary leadership in the academic world, then the shipping magnate C.Y. Tung (Tung Chao Yung) 董浩雲is a contemporary example of East Asian visionary leadership in the corporate world. Combining a Confucian commitment to education with modern philanthropy, he purchased the retired ocean liner Queen Elizabeth in 1970 with the intention of creating a floating United Nations University. He believed that ships carry ideas as well as cargo. His hope was that future students would develop a global perspective by travelling and studying around the world, and would cultivate a network of friends from all over the world whom they could draw upon when they themselves grew into positions of power and influence in their own countries. The United Nations University did not happen, but his dream lived on in the Semester at Sea program (七海大學), which he and the Tung family sustained from the 1970s to the 2000s and which remains one of the most transforming experiences of global education in the world.

Other examples of innovative institutions have appeared in Europe and the United States that have been remarkably successful in producing breakthrough innovations in the sciences and technology by applying the paradoxical principles noted above. Among the most prominent are the Bell Labs, the IBM labs, the legendary Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), and the Max Planck Institute. They were established outside the circle of universities, were well funded by their respective organizations, were managed by extraordinarily gifted leaders, and were deliberately given autonomy from control either by mid-management or by governmental agencies.

There are also a number of universities that have managed to overcome the natural limitations of the academy by deliberately embracing the paradoxes noted above. They were the subject of an intensive research study by University of Wisconsin historian J. Rogers Hollingsworth, who focused on institutional strategies that fostered major discoveries in the bio-medical sciences.[1] For more than a decade, he interviewed approximately 500 scientists who had received international recognition (such as the Nobel Prize) for their work. He also examined why it was that certain institutions produced far more major discoveries than their small size would otherwise have suggested. He discovered that the most successful institutions all seemed to share a short list of similar characteristics. They were small, decentralized, free of bureaucratic interference, cultivated a high tolerance for risk and failure, encouraged diversity, emphasized conversation and food in pleasant surroundings, hired passionate and visionary researchers, were well-supplied financially, and had remarkable (and extremely rare) leadership. These characteristics, in turn, manifested a high degree of complementarity—they formed interdependent variables, not independent variables. Among those most often mentioned in Hollingsworth's research are Rockefeller University and Cal Tech. He also gives considerable credit to Cambridge University, which has managed to find an extremely rich balance of big and small by giving wide autonomy to individual colleges to preserve their freedom of control over their own work, while leveraging the resources of the university as a whole when needed. The University of Chicago, founded with a donation from John D. Rockefeller, was yet another example of a remarkably innovative center of new ideas that emerged out of the philanthropy of wealthy donors. Not coincidentally, it was led in its formative years by two visionary, and surprisingly young, presidents: William Rainey Harper (who was 35 when he became president), and Robert Hutchins (who was 30). They were committed to the principle of interdisciplinary approaches to knowledge that still lives on at the University, though diluted by understandable pressures in the faculty over the years to replicate the standard academic model of hyper-specialization. In Copenhagen, the Institute of Theoretical Physics, founded by the legendary quantum physicist Niels Bohr with major funds from Carlsberg Beer and the Rockefeller family, was also successful in being both small and big, autonomous and integrated. Though affiliated with the University of Copenhagen, it retained a good deal of control over its own affairs.

It is interesting to note here that Japan and South Korea are trying to kickstart research institutes that incorporate many of the above characteristics. In 2011, Japan founded the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology with almost a $1b outlay.[2] In 2012 the South Korean government announced the creation of the Institute for Basic Science in Daejeon that was also intended to incubate a level of creative innovation that has until now eluded scientific research there.[3]Whether they will succeed only the future will tell.

Vision for the future

Given these conditions that have been successful in the past and present, how might we envision a research institution for East Asia capable of addressing the central issues of our time? What might such a research institute look like?

Retreat. I imagine a location for a research institute that would combine natural beauty, high technology, and innovative architecture designed to inspire imaginative and long-term thinking as well as extensive conversation, as does the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. The location of Zhu Xi's White Deer Grotto academy comes to mind as one example from the past of a research center situated in beautiful surroundings in the mountains of Lushan (廬山).

Leadership. Finding the right leadership would be central to the success of the project. It would have to be someone, or a group, with conceptual vision, widespread credibility in the East Asian region, and unusually developed human and communication skills, the contemporary equivalent of leaders like C.Y. Tung and Cai Yuanpei. Surely they exist. Perhaps they haven't yet been sufficiently inspired.

Small size. One of the principal criteria would be small size both in terms of personnel and buildings in order to foster conversation and avoid bureaucracy. A permanent staff would be necessary but there would be others who rotate in and out on a periodic basis, as well as conferences that would bring in leaders from throughout the region in political, social, economic, and cultural arenas for conversations.

Interdisciplinary. To overcome the artificial division of knowledge into the humanities, the social sciences, and the sciences, and to foster systemic thinking that would address problems in all the complexity that they deserve, the institute would be broadly interdisciplinary.

Diversity of participants. The goal would be to bring together people of widely divergent occupations, backgrounds, and perspectives, who are conversant not only in theory but in practice. This group would include political leaders with demonstrated vision, far-sighted journalists, thoughtful business executives, writers, academics, and thinkers and doers of all kinds. The operant principle is one stated by the Ming philosopher Wang Yangming 王陽明, namely that theory and practice form a complementary whole, zhixing heyi 知行合一.

NGO. A non-governmental organization would be more likely to maintain a sufficient level of autonomy to foster truly innovative thinking and tolerate the high degree of risk and failure that is essential for new thinking to emerge.

Periodic meetings. The research center might bring people together—maybe 20 at a time—for bi-monthly meetings in meetings conducive to conversation and interaction. Conversations could be captured and combined with a deeper level of research that would emerge from the conversations. Each of these rotating groups might have a life-span of one year, allowing synergy to develop but also bringing fresh ideas in every year that could build on and complement the conversations and insights of the previous year.

High level of technology. The technology of communication is changing with astonishing speed, making new opportunities possible that never existed before. While Chinese, Japanese, and Korean (and possibly English) might be the core languages of communication, there will be many individuals who are not fluent in all those languages. Fortunately, there are now emerging technologies of real-time translation being tested at Microsoft Research (among other places) that, when improved over time, might become an indispensable tool for this kind of research entity.

As a historian, I feel compelled to close by returning to something I mentioned at the beginning of this essay. East Asia is now, after two centuries, resuming its former role as the center of the world economy, which it held for almost two thousand years prior to the industrial revolution. With this newly recovered economic prosperity will come political power, and with political power will come new responsibilities for global leadership. To lead effectively, however, requires a vision for the future. It requires imagination. All the ingredients described above now seem to be in place in East Asia, many made possible by the miraculous prosperity of East Asian economies in the last half century. All that is needed now is some kind of institutional catalyst to convert these ingredients into a recipe for the future.

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank the Institute for Comparative Politics at the University of Bergen, Norway, and particularly the chair, Gunnar Grendstad, for their hospitality and support during the writing of this article in the spring of 2015, as well as Professor Siri Gloppen for letting me use her office for two months. I would also like to thank my wife, Wei-ping Kuan Wood 關蔚平, whose analytical and editorial skills as an attorney have saved me from falling off numerous logical cliffs.

Reference

1. Hollingsworth, J. Rogers and Ellen Jane. Major Discoveries, Creativity, and the Dynamics of Science. Vienna: Edition Echoraum, 2011.

2. http://www.economist.com/node/21540228.

3. http://www.nature.com/news/south-korean-research-centre-seeks-place-at-the-top-1.10667.